On Finding Our Soul's Vocation (James Hollis)

Listen now (62 mins) | “You said the important word there and that is the word grown up. To be grown up is what? To recognize, yes, I am accountable for what spills into the world through me..."

You can also listen to this episode on Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

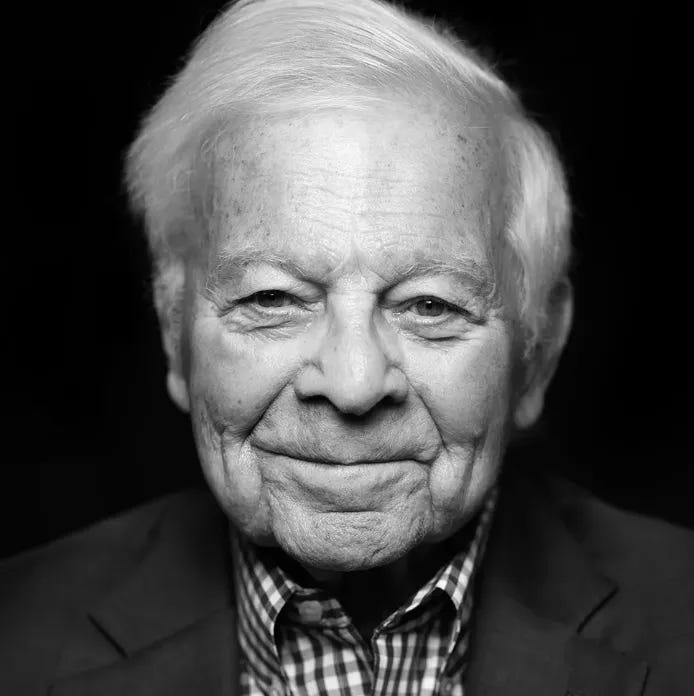

So says James Hollis, a PhD and Jungian analyst who is still in private practice in Washington D.C. Hollis started his career as a professor of humanities before a midlife crisis brought him to his knees—and to the Jung Institute in Zurich. The author of 19 books, Hollis i…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pulling the Thread with Elise Loehnen to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.