I recently read Moral Ambition by Rutger Bregman, a brilliant and straightforward Dutchman who has been making the rounds with people like Jon Stewart—and making the call to college graduates, to throw off the path to Goldman Sachs or a consulting career at McKinsey to pursue moral ambition instead. (As he writes, “Some 45 percent of Harvard alumni go into finance or consulting. A poll from a few years back shows that in my country of the Netherlands, 40 percent of ‘high achievers’ (college students with excellent grades) aspire to work for major consulting firms like McKinsey or the Boston Consulting Group.”) His point: The world needs all of its brilliant minds to focus on solving the world’s manifold problems. He is not wrong.

He’s coming up on Pulling the Thread, so read up in advance, and hopefully we’ll share common questions. If you already have questions, leave them in the comments below.

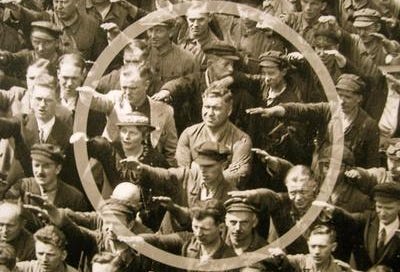

There’s a lot to remark on in this book, and I’ll definitely come back to it, but one moment that really caught my attention and feels incredibly true, is a tidbit of data from husband and wife team, Dr. Samuel Oliner and Dr. Pearl Oliner, who did research into the psychology of resistance in the 1970s. This is salient and essential for all of us who want to believe that we would have acted differently in the face of history’s abuses—that we would have been abolitionists, that we would have hidden Jews in our attics, that we would have spoken truth to power and suffered the consequences. First, some context.

For those who don’t know, the Netherlands has carried a bit of a reputation as a country of being fierce resistors to the Nazis. As Bregman writes, this isn’t exactly true.

In her wonderful Substack newsletter,

, the inimitable Tina Brown wrote this weekend about Sir Simon Schama’s new PBS documentary: The Holocaust, 80 Years On.She writes:

In Amsterdam, it was a slower, more bureaucratic version of the same story: a city that was a vibrant and safe space for Jews, for whom the Dutch expressed empathy when the Nazi persecution began, respectfully doffing their hats at a Jew compelled to wear a yellow star, until a general strike provoked a vicious Nazi crackdown and gradually, as Schama puts it, there was ‘a shriveling of the bravery ... and the most inclusive place in Europe for Jews became a place of exclusion and seclusion.’ By the end of the war, the highest percentage of Jews in all of Western Europe to be murdered was in the Netherlands. ‘The Holocaust can also come with gloves on, and that’s as horrifying in its own way,’ Schama says.

What will happen when the files of Dutch collaborators, currently being digitized, are released online to the public for the first time? ‘They were businessmen and mayors, civil servants, journalists, all kinds of people,’ Schama says. Their descendants will no longer be able to pretend they were resisters. ‘If Hitler had made it over the channel, there is absolutely no doubt it would have gone the same way,’ Schama told me, an observation that should make every living Brit’s hair stand on end. It grieves him that at a time when there has never been more Holocaust education there has also been a steep rise in its denial. According to the FBI in the US in 2023 there was an increase of 63% in antisemitic hate crimes. In The Holocaust, 80 Years On Schama confronted the monster, but have we?

In Moral Ambition, Bregman points to a tiny town that’s responsible for the Netherlands’ reputation as a country of resistors, a town called Nieuwlande on the German border. It was here that a man named Arnold Douwes convinced locals to hide and harbor 100 Jews. “The concentration of people in hiding was higher than nearly everywhere else in Europe,” Bregman explains.

In the decades since, many have tried to puzzle through what made these townspeople so brave and so resistant to the Nazis, in a country that was largely passive. What made them risk their own lives to save Jews?

As he writes,

“Even today, people in the Netherlands debate the question of whether we ‘gewusst haben’—whether we knew what the Nazis planned to do to Jews. But if you read about the people who resisted, you realize there are two forms of “knowing.” You can know something and then do something about it. Or you can know something and look away, afraid to face the consequences of what you know to be true.

“Those who helped Jews refused to look away. They believed they could make a difference. They didn’t see themselves as simple onlooker or cogs in the machine, but as autonomous people who could choose to do the right thing. They asked themselves the question, Can I live with myself if I do nothing?”

That’s an important question. And it’s the focus of the Oliners’ research. At first, they found nothing—they could find no traits that predicted whether someone would step up, or not. No psychological profile emerged, no suite of criteria. Nothing at all. Empathy didn’t even predict much: As we know all too well, there’s a vast chasm between awareness and action, which is a big theme of Bregman’s book. So many of us aspire to be activists and change-makers, but we stop at reading the news, yelling at people online, posting some things to our stories, and maybe showing up to a rally or protest. I am in this group, too. This isn’t how you build coalitions of change: Those require sustained planning and action, something that we don’t really have the wherewithall to do. (This is part of the focus of this week’s solo podcast episode—“How Do We Get Efficient with Our Energy?”—and I’ll come back to it soon.) Meanwhile, many of us change the channel or look away, which also happens in response to empathic overwhelm: There’s so much going on it can be difficult to figure out where to begin, or whether you can even make a difference. It is easier not to look, to stay busy, to stay out of it.

But, the Oliners did make a discover. It was just buried. Bregman writes, “[It] turns out there was one circumstance that determined almost everything. A new analysis of data gathered by the Oliners showed that when this condition was met, nearly everyone took action—96 percent to be precise. And what was the condition? Simple: you had to be asked. Those who were asked to help someone in danger almost always said yes. In many cases, the question seems to have been a turning point, with people then helping other Jews afterwards. And many who were asked to help went on to ask others.”

This is a topic for another newsletter, but as Bregman points out, we are highly mimetic—we often need someone else to move before we feel empowered to move too. It can be hard to be the first, in good ways and also in bad. (As Jesus says, “he who casts the first stone…”) Most of us need to be inspired to action. And the best way to inspire action, it turns out, is to ask. In the coming weeks, I want to turn my attention to the ask: Specifically, how do we create a meta-structure for organizing ourselves for action and then asking each other to jump in. How do we corral these asks and get to work? (For those of you who have listened to the solo podcast, who is doing this best? One friend recommended Red Wine & Blue.) All suggestions welcome.

I think the biggest tragedy of our civilization currently is we are allowing systemic violence to occur on our planet again. Have we learned no lessons from the Holocaust? The dehumanisation of the Palestinian people and the ensuing elimination of them is a genocide we are witnessing in real time beamed into our smart phones. Children starving in the streets because aid which is available is denied entry. Weapons and bombs sold without batting an eyelid for the consequences. The lives quenched and the lives changed beyond measure from the horrors that are perpetrated. Hospitals bombed, paramedics shot in cold blood. It is a stain on our civilisation and we will look back in future years and ask ourselves the same questions, who resisted? Who stood up and risked their livelihoods to say what is almost not allowed to be said in the mainstream.

I appreciate essays like this one which connect dots between past and present in a way that observes the overwhelm without shame and invites curiosity and introspection, which is perhaps how we get ready to say yes when the ask comes.