Oh, Mother’s Day. Another day during which women get to feel conflicted. I mean, I get it. I don’t really relish Mother’s Day—it’s typically a day like any other, which is honestly okay with me. After all, it’s a fabricated holiday, coined by a woman named Anna Jarvis in the early 20th century to honor her mother, Ann Reeves Jarvis, who organized “Mothers’ Friendship Day” in 1868 to foster reconciliation between Union and Confederate soldiers after the Civil War. Anna Jarvis herself never married and never had children, and she actually petitioned to have the holiday removed from the official calendar after it became commercialized. (A woman who was raised by her dad after her mother died during childbirth moved to create Father’s Day almost immediately after Mother’s Day was institutionalized, though it did take many decades for it to become recognized.)

What’s interesting to me about the holiday is how many of us feel bad about it, and how these feelings of badness have escalated over the years—or perhaps they’re more pronounced because of social media. We feel bad, because if we’re mothers, we likely find the day slightly embittering (sad deli flowers as some sort of compensatory measure for a year of largely invisible labor just feels bad…basic, ongoing gratitude feels better). We feel bad, because if we’re mothers, we’re reminded how many women want to be and aren’t able to become moms (yet). We feel bad because those of us who have living mothers are reminded that some peoples’ moms are on the other side, and are greatly missed. We feel bad because if we have a great mother, we’re reminded that some people had ones who were difficult, distant, mean. And now, with waning bodily autonomy and movements to forcibly remove the freedom to choose happening across the country, we’re reminded that while we might have chosen to have children, many women are now being forced to become mothers, despite not wanting to (or having to risk their lives in the process).

I have never seen a man post on Father’s Day that he feels awkward celebrating his dad because he wants to honor all the men who had absent or tough fathers. Or that he feels self-conscious being celebrated publicly because he does not want to trigger all the men struggling with infertility. This just doesn’t happen. I’m not sure if it should or should not, but its absence feels remarkable.

I don’t think men wrestle in the same way as women do with feelings of “badness” and consequently “goodness.” I don’t think they’re particularly concerned with being called out as insensitive for not taking everyone’s feelings, however complex, into consideration. (I don’t actually think they’re even much thinking about these things.) Being a woman is awfully hard. We struggle to cut ourselves and each other slack. If there’s something to police ourselves about, we rush to do it, before someone does it on our behalf.

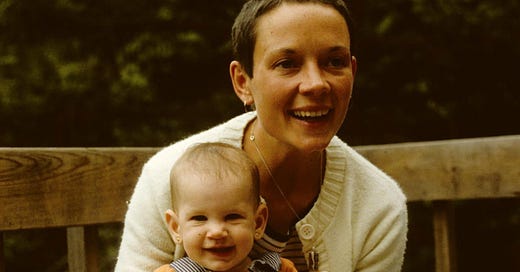

I wrote about my mother a fair amount in On Our Best Behavior—and she’s become an object of fascination for my publishing team. (They want me to interview her for Pulling the Thread, stay tuned.) I wrote about her for a piece coming soon, too, which I’ll share with you later this week. In a nutshell: My mom is fascinating, brilliant, and complicated—a box of See’s Chocolates doesn’t really do the relationship justice, or what she’s done for me. Neither does one day a year. And I chafe at the idea that it should.

Switching gears for a second, I spent part of this week with a friend named Courtney Smith, who coaches the Enneagram. (She’s a Yale Law school grad, has a Masters in Public Health, majored in mathematical engineering, and is a former McKinsey consultant—gah! She really makes me work to keep up with her intellect, but she also makes me laugh really hard. And can I say how much I love it that she took a hard left turn into esoterica?) We stayed up really late one night talking about the most helpful frameworks in her practice and she took me through the dynamics of the Drama Triangle, which I’d heard of via Roshi Joan Halifax’s Standing at the Edge, but have never studied.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pulling the Thread with Elise Loehnen to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.